A

A

![Cap Coleman's tattoo parlor The Legendary August "Cap" Coleman's Tattoo parlor in Norfolk, Virginia --1936.]()

The Legendary August "Cap" Coleman's Tattoo parlor in Norfolk, Virginia --1936. photo by William T. Radcliffe © The Mariners' Museum/Corbis

A

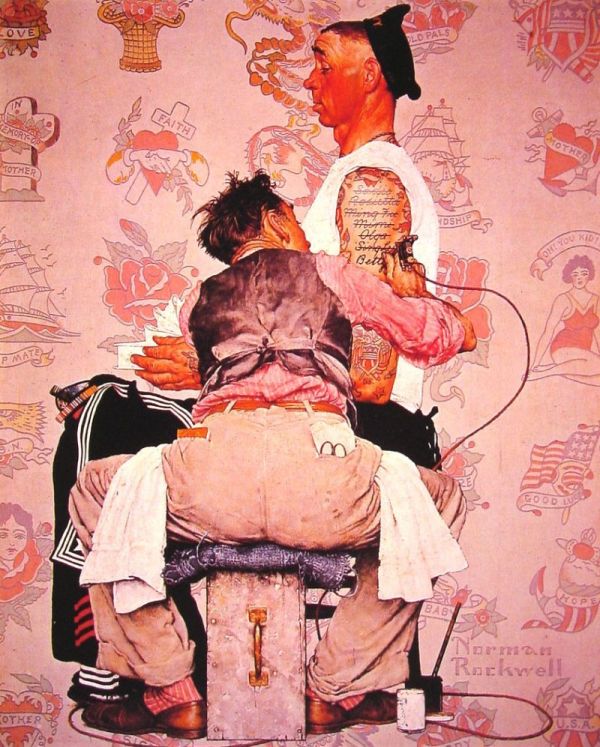

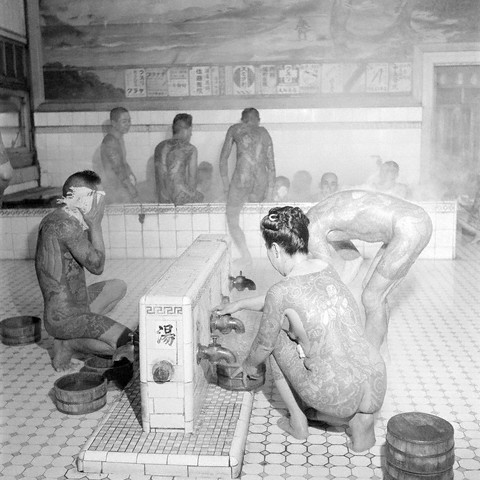

Before Ed Hardy and even Sailor Jerry, there were a couple of guys who are widely considered the forefathers of American Tattooing– August “Cap” Coleman, and the youngling he heavily influenced and mentored, Franklin Paul Rogers. When you trace the history of tattooing, a good chunk of the great flash icons can be traced directly back to these American masters. They blazed a counterculture trail back when the only guys (and gals) that sported body ink were either in the service, criminals, or circus and sideshow freaks. Tattoos were not taken lightly. Nowadays, ink has lost some of it’s original rebellious sting– but for the bearer, it often represents a deeply personal story and is worn like a badge of honor.

A

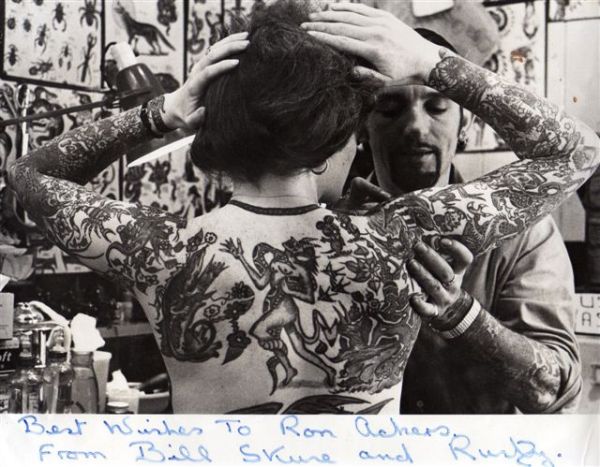

![August "Cap" Coleman "August "Cap" Coleman personally manned his legendary tattoo parlor six days a week.]()

August "Cap" Coleman personally manned his legendary tattoo parlor six days a week --circa 1936. photo by William T. Radcliffe © The Mariners' Museum/Corbis

A

Not much is known about August “Capt.” Coleman’s early years– born in 1884, somewhere near Cincinnati, Ohio. He like to boast that his father was a tattooist as well– but it’s not known for sure, and even Paul Rogers doubted that story. It’s not even clear who was responsible for the handiwork displayed on Coleman himself, but some of it was more than likely done by hand. In fact, much of the original artwork behind Coleman’s personal tattoos can be seen on an old statue that he later displayed.

What is known without a doubt is that around 1918, “Cap” Coleman dropped anchor in the navy town of Norfolk, VA and set-up shop in a particularly salty spot on Main Street well known for strip clubs and sailors– there was no shortage of action or customers. The rest as they say is history– “Cap” Coleman wasted no time in becoming a living tattoo legend. The shop was so well known, he didn’t even bother to list the address on his business card.

In 1950, tattooing in Norfolk was declared illegal. After 32 years in Norfolk, Coleman relocated across the Elizabeth River to Portsmouth, Virginia– opened up shop and continued his practice.

Then sadly in 1973, Coleman’s body was discovered in the Elizabeth River. Authorities suspect that he slipped and fell into the river. It turned out Coleman was quite the savvy investor, and had amassed a small fortune– which he generously left to several local charities including the Virginia School for the Deaf, the Norfolk United Fund, the Tidewater Lions Club, and the St. Mary’s Infants Fund.

A

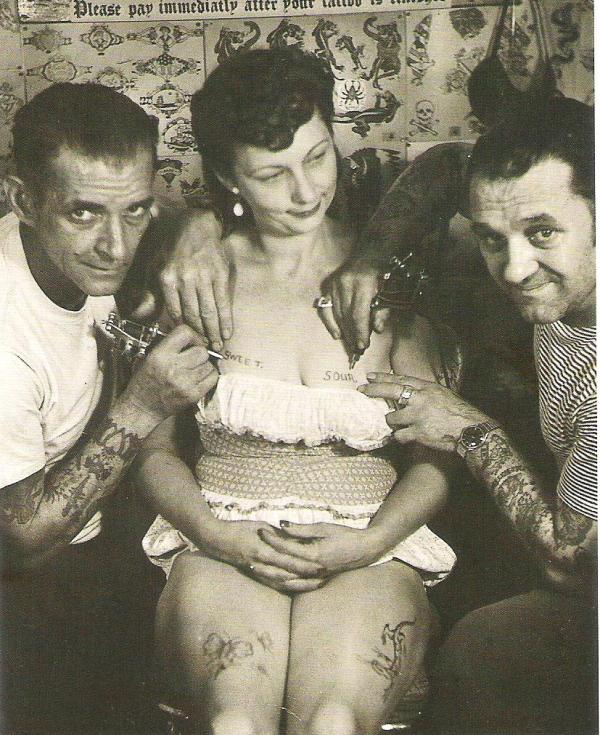

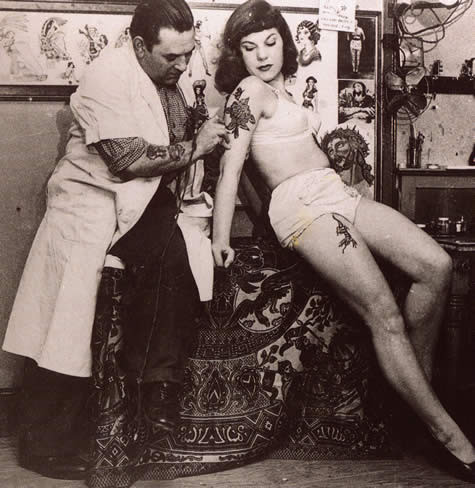

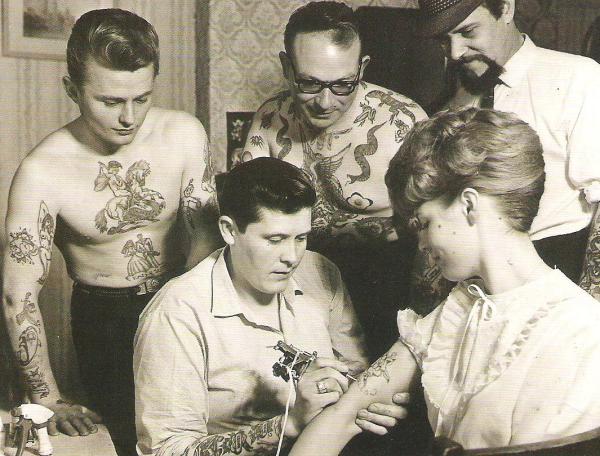

![Franklin Paul Rogers tattooing his wife Helen-- 1936. Franklin Paul Rogers tattooing his wife, Helen-- circa 1936.]()

Franklin Paul Rogers tattooing a gal believed to be his wife, Helen-- circa 1936.

A

From “Paul Rogers– The Legend Lives Forever” by Tim Coleman, Skin&Ink magazine archive–

Paul Rogers’ influence on tattooing is immense. Rogers is the bridge that connects the best of the old-school American traditional tattooing to some of the most accomplished artists of the modern renaissance. Tattoo giants such as Don Ed Hardy, Greg Irons and George Bone, to name but a few, have all benefited not just from his over 50 years in the business, but also from the remarkable sophistication of the machines he designed, universally acknowledge to have been the best money could buy. Rogers later formed a partnership with Huck Spaulding establishing one of the most famous and highly respected tattoo supply companies in the world, Spaulding and Rogers.

American tattoo archivist Chuck Eldridge, who inherited Roger’s entire collection after his death in 1990, believes that Rogers’ contribution to U.S. tattooing was unique. “He was a vital conduit of information and experience,” says Eldridge. “Between 1945 and ’50, Rogers worked with Cap Coleman, who at the time was considered one of the best tattooists in the world. During this period he gained much of his knowledge about how to make and tune tattoo machines from Coleman and another tattooist, Charlie Barr.” Eldridge believes that it was this transference of knowledge about machines to the modern generation of U.S. tattooists that makes Roger’s contribution so significant.

Tattooist and archivist Don Lucas, who published Rogers’ autobiography Franklin Paul Rogers: The Father of American Tattooing, agrees with Eldridge.

“Without Paul’s willingness to share his knowledge and talent for building the world’s best tattoo machines, the hard learned secrets of the past masters would have been lost in time.”

A

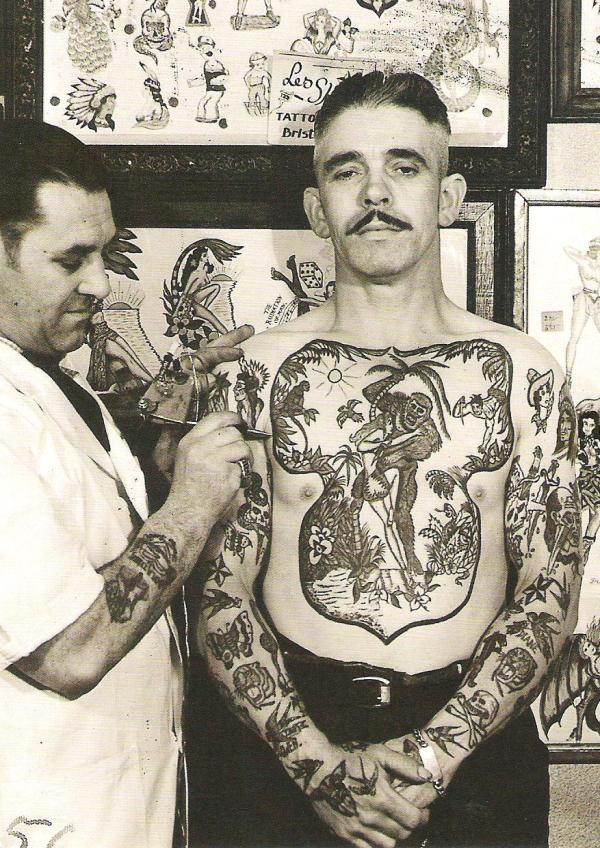

![Franklin Paul Rogers tattooing a sailor --circa, 1940s. Franklin Paul Rogers tattooing a sailor --circa, 1940s.]()

Franklin Paul Rogers tattooing a sailor --circa, 1940s.

A

Rogers was born 1905 in the mountains of North Carolina. The family of five children lived in a log cabin in the woods. His father earned a living as a timber cutter. Rogers describes his first seven years as one of hardship and poverty, “but a way of life and what life is all about.” He spent much of his childhood moving from one cotton town to the next, as the family sought employment in the dehumanizing conditions of the cotton mills. This was a period of totally unregulated capitalism, and child labor laws didn’t exist. Rogers started work in the mills at 13 and continued up until 1942. On average, Paul earned $3.50 a week. In his autobiography, he states, “It was nothing but hardship. It was hard for everybody.” Fortunately for Rogers, he discovered tattooing and a way out of the stifling conditions of the mills.

Rogers’ first got interested in tattooing when a traveling salesman visited the log cabin, when he was still a child. He was struck by the design and the tall tales the man told of his time in the army during the Spanish-American war.

A

![A service woman has a tattoo done on her arm, Aldershot, 1951 A service woman has a tattoo done on her arm, Aldershot, 1951]()

![December 1944, aboard the U.S.S. , Pacific Ocean --- A sailor aboard the U.S.S. inspects another sailor's tattoos. December 1944, aboard the U.S.S. , Pacific Ocean --- A sailor aboard the U.S.S. inspects another sailor's tattoos.]()

A

In 1926, aged 21, Rogers got his first tattoo from Chet Cain, a tattooist who worked with one of the traveling circuses. It was through Cain that he first heard about Cap Coleman, the tattooist who he was later to work with and who had such an influence on his life. Cain gave Rogers some advice on tattooing, and two years later he began to tattoo. “I bought a tattoo kit in 1928,” he writes in his autobiography. “It was a kit from E.J. Miller. He had a supply place in Norfolk, Virginia. It ran off dry-cell batteries.” Rogers found out about the tattoo supplier through his interest in the traveling circuses. He had seen an advert for it in Billboard, the well known U.S. entertainment magazine. “I always wanted to travel with a circus,” he stated in an 1982 interview with Ed Hardy in Tattootime. “I decided to learn how to tattoo and travel with the carnival and work on the sideshow.”

As well as learning how to tattoo, Rogers trained hard in acrobatics. “I used to train religiously,” he stated. “Even when I started tattooing, I still trained. I have always been interested in the physical end of things.” He was also very careful how he treated his body. He never smoked, drank coffee or touched alcohol.

A

![Tattoo George Burchett demonstrating tattooing in a UK series, host S.P.B. Mais is at right --1938.]()

George Burchett demonstrating tattooing in a UK series, host S.P.B. Mais is at right --1938.

A

Rogers began tattooing from his bedroom, experimenting on himself and any willing neighbors. But he soon ran out of flesh and, in his search for new customers and experience, joined one of the traveling circuses. In 1932, he worked on his first sideshow in Greenville, South Carolina, where he vividly recalls striking up a friendship with the three-legged man. “He was fun to be around,” mused Rogers in Tattootime. “He used to kick a football with that there third leg. He said that, when the streetcar was crowded, he would use that extra leg for a seat. He could sit on it like a stool.” Later that year, Rogers joined the John T. Rae Happyland Show where he met his wife, Helen. She was working as a snake charmer. Rogers spent seven months of that year traveling around in a Model T Ford and living in an “umbrella” tent. “I had a ball,” he told Ed Hardy. “But I only grossed $247. So, I guess I ate a lot of peanuts that year, “he recalled, laughing.

Rogers explained that during that period many tattooists made their living working with the traveling shows. This was during the great depression and times were extremely hard. Throughout the 1930s, to make ends meet and to help support his wife and two children, Rogers would spend his winters working in the Cotton Mills and the summers tattooing with the circus. Helen’s stepfather owned the Happyland show, so the family worked together. Rogers recalled that, initially, the circus owners wanted the tattooists to double as the tattooed man and be on display, but later Paul was able to work purely as a tattooist.

As well as working out of a mobile tattoo studio, Rogers also worked in an assortment of poolrooms as well as army boot camps. “In Spartenburg, South Carolina, I worked in a combination shooting gallery and shoeshine place with a jukebox,” he recalled. “They sold hot dogs and bootleg whisky and had card games going on. They had it all covered.”

A

![Tattoo van Edward Vanderwerer, known better as "Tattoo Van" a member of the World of Mirth Carnival, as he shaved before his appearance as a carnival attraction, May 8th, at Alexandria, Va. Vanderwerker is compelled to shave very closely in order that his face maintain the detail of the tattooing. He has also had some tattooing done on his scalp --1937.]()

![tattoo lady tattoo lady]()

A

In 1942, Rogers got a chance to get off the road and set up his own shop in Charleston, South Carolina. A friend and fellow mill worker F.A Myers, who had taken up tattooing, invited Rogers to go into a partnership. Up until that time, Rogers’ largest pay packet from millwork was $42 for a 40-hour week. Once he got his shop up and running, Rogers was able to make up to $200 a week. At last he was able to forever turn his back on the exploitation and slave wages of the mills.

It was during this time that Rogers saw many examples of Cap Coleman’s tattooing on the sailors who came through the shop. Rogers immediately recognized Coleman’s work, as it was far superior to any of the other tattooists working at the time. “I patterned myself after him,” he explained to Ed Hardy. “I used to copy any tattoo I could off the sailors.” Rogers would use celluloid sanded on one side, so the rough surface would grab a pencil lead. This way he could make to make a copy of Coleman’s tattoos. “I got a copy of a Panther head that way. A panther climbing an arm, that was a new thing back then. I would try and duplicate it. Shade it the same way Coleman had.”

Cap Coleman first became aware of Rogers’ tattooing from a sailor. Rogers explains the story. “Coleman would always say to the sailors, ‘You haven’t got a good one on you.’ It was his way of getting them to get one of his tattoos. So, he twisted this guy’s arm saying, “There’s one I did and there’s another.” But the sailor told him, ‘This isn’t one you did.” Coleman was amazed that anyone could tattoo well enough for him to confuse it with one of his own.

A

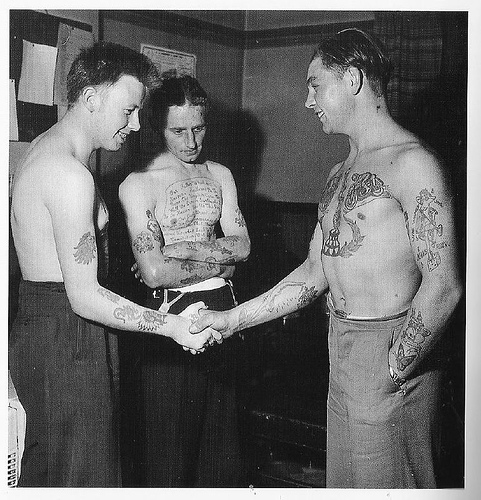

![Sailor tattoo Storytelling time aboard the U.S.S. Texas found S.O. Buchanan, tattooed wonder of the crew, surrounded by shipmates --1928.]()

Storytelling time aboard the U.S.S. Texas found S.O. Buchanan, tattooed wonder of the crew, surrounded by shipmates --1928.

A

Later Rogers wrote to Coleman and then visited his shop in Norfolk, Virginia. Coleman then offered him a job in his shop, once the war was over. “It was the job offer from heaven,” explains Eldridge. “You have to remember that Coleman was considered one of the best tattooers in the world at that time. It’s like Ed Hardy offering a job to some 20-year old, hotshot tattooist. Who would turn that down, given all the fantastic things one could learn?”

In 1945, Rogers began a five-year association with Coleman. Coleman had been tattooing since 1918 and was so well known that he didn’t even put his address on his business card. Coleman’s studio was strategically located on Main Street, next to an old striptease and burlesque house commonly frequented by sailors. Norfolk was a navy town, so there was no shortage of customers. Rogers recalls Coleman with mixed feelings. He was in no doubt that Coleman was one of the greatest tattooist in the world, but he was certainly not in awe of his personality. “He was a very selfish guy,” remembered Rogers. “He would never give anyone the time of day. Coleman was a people hater. Quite the opposite of me, I was everybody’s friend. He was sort of a hermit and practically lived in the shop. He kept canned food there, so he wouldn’t have to go out. And he would have a can of tinned spinach for breakfast!”

In order to save money, Coleman would tell service men that he couldn’t use brown or green inks in the tattoos, if they had been vaccinated. He told them it would make them sick. “That way he got by using just black and red all the time,” recalled Rogers. “Black and red, black and red.” Despite these sly tricks Coleman was able to apply high quality work. His work was clear and well shaded. Consequently, his tattoo designs epitomized what came to be known as the classic American-style tattooing that dominated the 1920s to the 1940s.

A

![Outlaw biker tattoo Case involving members of "Outlaws" motorcycle club, who are accused of nailing a female member of their club to a tree for holding out $10. Mrs. Bertha (Kitty) Randall and tattooed biker Donald "Deke" Tanner inside her bar --West Palm Beach, FL 1967.]()

Case involving members of "Outlaws" motorcycle club, who are accused of nailing a female member of their club to a tree for holding out $10. Mrs. Bertha (Kitty) Randall and tattooed biker Donald "Deke" Tanner inside her bar --West Palm Beach, FL 1967. Hey man-- ten bucks is ten bucks. Check the iconic panther tattoo on Deke's right arm.

A

Despite Coleman’s eccentric personality, Rogers learned a great deal about tattooing from him, especially about machines. Prior to working with Coleman, Rogers had to learn everything the hard way, through trial and error. While working for Coleman, Rogers began fixing the machines for all the tattooers working in Norfolk. “There were 11 of them at one point,” he stated. “And you could count the good ones on three fingers.”

In 1950, Rogers’ association with Coleman came to an abrupt end. The city of Norfolk decided to ban tattooing. This forced most of the Norfolk tattooists across the Elizabeth River to Portsmouth. Rogers eventually formed a partnership with R.L.Connelly, a talented tattooist who worked briefly with Coleman. The two set up shops in Petersburg, Virginia and Jacksonville, North Carolina, with Rogers eventually owning the Jacksonville shop.

A

![tattoo woman tattoo woman]()

![tattoo lady tattoo lady]()

A

While working in the Jacksonville shop, Rogers met Huck Spaulding. Rogers described Spaulding as ” a real scratch artist,” a tattooist with very limited experience who had worked a little in the traveling sideshows. Rogers helped Spaulding improve his technique and when, in 1955, the studio Rogers and Connelly used was torn down, Rogers moved into Spaulding’s shop half a block away on Court Street, giving birth to the now famous name of Spaulding and Rogers. This shop became home to the famous supply business that is known worldwide.

What immediately distinguished this mail order supply business from its competitors was a commitment to high quality. Ed Hardy first noticed the company when he saw an advert in the back of the magazine – Popular Mechanics. Most of the best tattooists of that time started ordering through Spaulding and Rogers. A trend that continues to this day.

A

![tattooed lady tattooed lady]()

![tattoo lady tattoo lady]()

A

Rogers only worked in the supply business for two years. He continued tattooing with Spaulding for four, but then in 1963, he moved to Jacksonville, Florida to tattoo with Bill Williamson. In 1970, Rogers and his wife, Helen, bought a mobile home and it was there that Rogers found much more time to focus on what he wanted to do most: improve existing tattoo machines and design new ones. In a portable 12-by-12-foot tin shack affectionately called “the Iron Factory,” Rogers spent all his time making unstylish but incredibly dependable machines. The now popular slang for calling tattoo machines “irons” derives from Rogers, who first coined the word.

During the 1970s, Chuck Eldridge befriended Rogers and spent much of this time with him at his home in Jacksonville. “Paul was from the old school,” states Eldridge. “His machines were built almost entirely with hand tools. Machine heads from around the world would gather in that small shed and hang on every word, hoping to gain some of Paul’s understanding.” Eldridge is keen to emphasize just how important the working of a tattoo machine is. “It’s a very subtle device. And it’s vital for a good tattooist to have a machine that is properly designed and balanced. It’s impossible to execute high quality work without this. It’s an absolute prerequisite. Why do Ferraris have such a great reputation in car racing? Because they win races, and you can’t do that without fantastic equipment. Its exactly the same with Paul’s machines.”

A

![sailor tattoo sailor tattoo]()

![circus lady circus lady]()

A

Ed Hardy is equally enthusiastic about emphasizing the impact Rogers’ machines have had on the development of tattooing. “I think it would be amazing to see a catalogue of all the different styles of tattooing that are being done with the machines Paul made or re-worked,” he states. “That way, you could actually get an idea of how important Paul’s contribution has been.”

In 1988, when Rogers was working on his autobiography, he had a stroke and was rushed to hospital. Later he suffered another stroke that paralyzed his right side and deprived him of his ability to speak. Ironically, the stroke occurred on the 60th anniversary of the day he began tattooing. He died two years later in a nursing home at age 84.

A

![Tattoos Tattoos]()

![tattoo tattoo]()

A

In 1993, Chuck Eldridge formed a non-profit corporation along with Ed Hardy, Alan Govenar and Henk Schiffmacher (Hanky Panky), the Paul Rogers Tattoo Research Center (PRTRC). This organization was the recipient of Rogers’ entire collection of tattoo memorabilia, flash and photographs. Unlike many tattooist who buy collections and keep them to themselves, the aim of the PRTRC is to raise money to establish a museum and research center. This center will then house the complete Rogers collection. “So far we have raised around $30,000,” states Eldridge. “The target amount is, of course, limitless but, initially, we need enough to put a down payment on a property, so we can create this landmark.”

Unfortunately, property in the San Francisco Bay Area, where Eldridge’s studio is located, demands some of the highest prices in America. “If we can’t find a building here,” states Eldridge, “we’ll take the collection back to North Carolina. It’s where Paul came from and would be the right thing to do. It would be like taking Paul home.”

A

![Paul Rogers tattoo Examples of tatoo legend Paul Rogers' work.]()

Examples of American tattoo legend Paul Rogers' work.

A

![Paul rogers tattoo flash Examples of American tattoo legend Paul Rogers' original flash.]()

Examples of American tattoo legend Paul Rogers' original flash.

A

A

![]()

![]()